Chaga: A Remedy for Winter

Of all the stately trees native to the Northeast, it is hard not to take a special liking to the paper birch (Betula papyrifera). Its peeling ivory bark, which happens to be an unparalleled fire starter, reveals a mini-sunset of yellow, salmon, and purplish hues on closer examination. Though it is native throughout the Northeast, the paper birch is most common in the Northern part of the region, where its cold hardiness gives it a competitive advantage. I recently moved to Burlington, VT, putting me in prime birch country.

If you live in this neck of the woods, you can take part in a special winter mushroom foraging ritual: the hunt for chaga (Inonotus obliquus), a powerful medicinal growing on older paper and yellow birch trees. Of course, if you have access to a nice birch grove then you can search for chaga during the summer months as well.

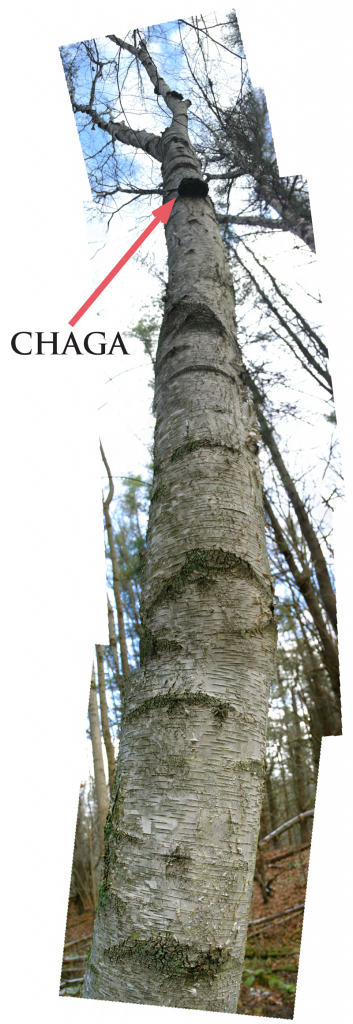

But let’s be honest: when the black trumpets and chanterelles are peaking, your eyes are going to be glued to the forest floor. Chaga is not the kind of mushroom that grows at the base of its host tree, like maitake. Instead, chaga typically grows in the middle to upper reaches of the birch’s trunk, meaning the medicinal mushroom forager must look up just as much as down.

I was probably doing a bit too much looking up on a backcountry ski yesterday at Bolton Valley, when I flew off an unexpected mini-cliff and dislocated my shoulder. But hey, I did spot a couple nice chaga specimens, so perhaps it was all worth it.

In the winter, all the ground-dwelling fungi are gone, so you can embark on a focused hunt for chaga by training your gaze upward and looking for black, charred-looking growths (called sclerotia) on the pale bark of paper birch trees. The leafless branches make it easy to spot chaga from far away – just look out for what appears to be a snow-capped black koala bear hugging birch trunks.

Ari aims his forager's eyes upwards into the birch canopy.

You may need a ladder to reach your chaga, as well as a sturdy implement to harvest it. Now that I’m living in the North Country, I may have to pick up a hatchet to throw in my backpack on skiing forays along with my requisite Nalgene and PB & J.

Chaga usually grows on older but still living birch, so take care not to scar the tree as you collect your medicine. Responsible harvest of chaga does not harm the tree, as it is a parasitic fungus only found on birches that are already past their prime. It is of more benefit to you than it is to the host tree – like the revered reishi, chaga is a panacea with reputed antitumor, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-hyper-glycemic properties.

I also spotted the arboreal artist’s conk on my ski yesterday, but this perennial fungus loses its medicinal potency when the cold sets in. Chaga, however, retains its full medicinal value year-round, making it the only outlet for my foraging fanaticism in the dead of winter. When you return from your winter wandering with a satchel full of chaga, a hot cup of chaga tea will be just the remedy you need.

A bluebird day is a good excuse to go on a chaga foray!